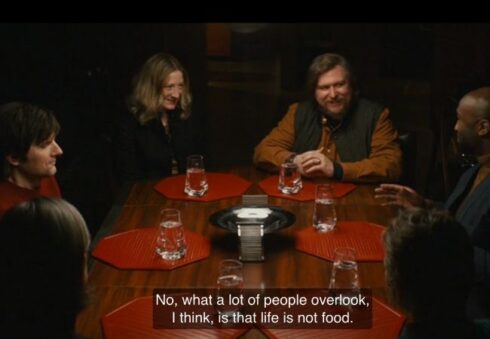

SEVERANCE The meaning behind the foodless dinner

The Apple TV+ show Severance is deliciously woven with intricate details delving into complex concepts about memories, selfhood, personal autonomy, and work/life balance (to name a view.) One of the unique ideas is a trend in the world of the show where people meet up for foodless “dinners” where they serve only water. The point of the meeting is to see at a table and have discussions like people would have over dinner but without the bonding of “breaking bread” together or the social lubricant of alcohol (or even the sugar rush of something like juice or soda.)

This situation is jarring because it takes the joy of “dinner” completely off the table (pun intended) while highlighting how bland, erroneous, and even dangerous exchanging information with people can be. The emptiness of this food-free dinner is symbolic of how empty social interactions can be.

“What a lot of people overlook, I think, is that life is not food,” one dinner guest explains as another agrees “Right.”

But is life not about food? Without food how do we even sustain life? Isn’t life just one big energy and chemical exchange between different life forms?

“You’ve got life, this complex quality of sentence and activity,” the guest continues, making very little sense. “And then you’ve got food, which is what?”

“Yes, what is it?” asks Mark’s brother-in-law Ricken.

“Fuel!” the guest says. “Calories. It’s not the same thing.”

As the other guests agree with this thought, Mark frowns and slightly shakes his head to indicate he’s not on board with this idea.

This same character later interjects, when he hears that Mark used to teach World War I history, by sharing a tidbit from an article he’s been reading. He’s immediately congratulated for being a “nerd” before he puts his foot in his mouth by saying something inherently rather stupid, especially in front of a World War I expert. He claims that during World War I it was considered a faux pas to call it World War I. Instead, they called it The Great War.

Mark points out what should be obvious: World War I wasn’t called world World War I at the time because no one knew that there would soon be another “Great War.”

This type of conversational exchange, of sharing information to appear smart, information that may not even be accurate, is a common social practice, and a part of the act of socializing over “dinner.”

Later, when the topic of Mark’s severance comes up one guest asks Mark what it feels like. She wants to try to understand the “visceral” element of what he’s experiencing.

Again, the know-it-all guest who has separated the concept of food from life, and thought that it had been a faux pas to call World War I by the name we know it by now when it was happening, jumps in to explain how “simple” severance is to experience, despite not having any real knowledge or experience on the subject.

“Well, it’s simple,” he says. “One’s memories are bifurcated so when you’re not at work, you have no recollection of what it is you do there.”

“Did I get that right, Mark?” he asks, looking for approval and validation for his surface-level summary of what has happened to Mark. While Mark starts to try to explain further, he’s interrupted by another guest.

“And conversely when you’re at work you can’t access outside memories,” the know-it-all guest continues. “So, in effect, that version of you is trapped there. I mean, not trapped, but . . .”

“But what?” Mark asks, shutting down the conversation. “No, no. I’m curious. What were you gonna say? Not trapped, but what?”

One guest remarks that they know where Mark stands on the congressional situation regarding the legality of severance, which is being fought on a state-by-state level. Before the conversation devolves into political chatter, Mark’s brother-in-law Ricken steps in to say that he supports Mark in his very controversial decision leading others in the group to echo that they support Mark as well.

Ricken then goes on to say that usually at this point in the dinner, he would ask the guests to “dig in,” but says he feels that they have already dug in on a much deeper level. This isn’t true, however. No one at the table has engaged in any kind of deep conversation or communication. Very little of substance has been said and most of the guests simply agree with every opinion that is presented.

Throughout the entire dinner, Mark is alienated from the other guests. He is alone in his grief over his wife Gemma, and in his life as a human science experiment. Every deep topic is skimmed over and the conversation is as bland and colorless as the water set before them at the table.